Timing the Real Estate Market is Impossible

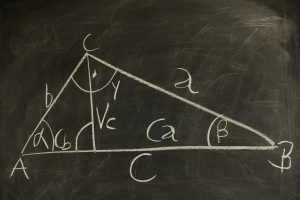

Squaring the circle.

Doubling the cube.

Trisecting an angle.

There’s one more impossible problem to add to the three traditional ones of Greek antiquity.

Timing the market.

It took the world’s brightest minds 23 centuries to prove that no one can construct a square with the same area as that of a given circle. Yet people have insisted on trying to time the market for at least that long. (With results far more predictable than the market itself.)

Handicapping the Race When It’s Over

With hindsight, timing the market is the easiest thing in the world. Regarding real estate, all you have to do is buy every property you can get your hands on in 2000, sell them all in the spring of 2006, and again buy as much as you can 3 years later. It’s a foolproof strategy, except for the tiny sticking point that time proceeds in the opposite direction.

The proverb “The good is the enemy of the best” applies perfectly here. The temptation is often to chase that one potentially perfect investment, the one purchased for the absolute lowest theoretical price and eventually sold for a price as close to infinity as possible. Which means timing the market, which means predicting the net result of the activity of millions of people exchanging tens of thousands of properties, which we’ve already established that no one can do.

Focusing on the elusive goal, the ne plus ultra of investments, means letting less perfect but still lucrative opportunities pass you by. No truly successful investor tries to be the best. But plenty try to be merely good.

Want a real-world example? Sure, you can buy a dozen 3-bedroom houses in Highland Park, Michigan for a total of less than $50,000. You won’t find any cheaper, anywhere. Then, all you have to do is wait for the neighborhood – consistently one of urban America’s most rundown – to gentrify. But you could well be waiting decades. Better to take that $50,000, use it as a down payment on a modest multifamily property in an up-and-coming area, a property that’s selling at a little if not a lot below market value. Then bank on the likelihood that the area will continue to improve. The chance of ruin in the second example is considerably smaller than it is in the first. But that microscopic chance of stupendous profits in the first is what turns some people on to real estate investments that end up being disastrous. A lottery ticket, even one that takes the form of non-condemned housing in a weak location, is not an investment strategy.

A Watched Portfolio Never Boils

Of course you should pay attention to the fluctuating values of your investments. It seems almost tautological, but that’s how you know how well they’re performing. But if you’re obsessing over the state of the market in general, worrying every time the Fed announces a rate movement or the housing index moves 10 basis points in one direction or the other, well, that’s not the behavior of an investor who’s committed to long-term growth. It’s the behavior of a speculation addict looking for his next high-return fix.

A little information is a good thing. A lot of information can be, and often is, paralyzing. There is indeed such a thing as too much data, and once you reach that level, you can always find some indicator that bears however tenuous a connection to your eventual decision to buy, sell, or hold. So what to do?

You can’t unlearn, but you can prioritize. Understand that despite the bombardment of information that comes from living in 2016, certain truths remain as timeless as mankind’s inability to trisect an arbitrary angle using just a straightedge and a compass. “Buy low” isn’t some newfangled piece of esoteric investment advice, group-tested and vetted by a gaggle of quants before being cited in an academic journal. Far from it. In fact, it’s the only logically consistent way to invest.

Start with the assumption that while you might have your educated opinions, you cannot predict the market’s zeniths nor its nadirs. Then take solace in the truth that no one else can, either. Invest irrespective of external goings-on that you can’t control anyway, and couldn’t control even if you were Warren Buffett or Donald Bren (America’s largest individual real estate investor.)

Know Where You Stand

Some especially overconfident real estate investors, assured of their own brilliance, love to speak in terms of which “inning” of the game a particular investment or sector is in. The thinking goes that an investment’s value will rise gradually, only for its potential to end abruptly (the final out of the 9th inning). Thus, the thinking goes, a shrewd if not omniscient investor will liquidate and find a more suitable investment before the game’s over.

Where the analogy breaks down is that sometimes the game goes to extras. Or gets suspended thanks to a rain delay. Worse still, it could well be a minor league doubleheader game, which goes only 7 innings. Cycles, when they exist, don’t do so on a schedule.

Do you know how to calculate a cap rate? Or how to measure the typical volatility of a certain class of assets? Or how to compare your likely range of returns with that of other types of investment? That’s not a sufficient condition, but merely a necessary one for building wealth via private equity investments in real estate.

The Final Word

Buy undervalued assets. Short of inheriting, that’s the quickest, easiest, and most certain way to wealth. There is no market where that strategy doesn’t apply. As a bonus, it reduces the problem of predicting the market’s peaks and troughs to the much simpler problem of figuring out what constitutes an asset that’s selling for less than market value.

At any given moment, some commodity, somewhere, is on sale. Especially in the real estate market, which is really a collection of disparate markets: Manhattan office space, Wyoming ranchland, suburban Dallas industrial parks, etc.

Even for the committed investor, it’s impossible to stay on top of the daily machinations of every one of those markets. A truly wise real estate investor knows to delegate responsibility to the specialists. People who’ve made it their lives’ work to diagnose opportunities, measure them and seize them.